This is an excerpt of an article that originally appeared in GQ in the USA in April 2018. Illustration by Guy Shield.

In late January, when we met for the first time, that image included a flannel shirt, beat-up trousers, and flip-flops. Chouinard is an unlikely nominee for wealthiest man in the room. He walks with an air of deflection, as if to duck attention. “It's funny, the first time I met him,” the celebrated mountain climber Tommy Caldwell told me, “I walked into the cafeteria at Patagonia, and I was like, ‘That guy looks like a homeless dude.’”

Chouinard is both a beatnik dropout and a renegade capitalist. A revolutionary rock climber in his day, who still disappears regularly to surf and fly-fish, he oversees a corporation that did $800 million in sales last year. At 79, Chouinard looks like a recovering mountain troll who enjoys sunshine, food, and wine but will probably outlast the rest of us if the apocalypse hits tomorrow. “I've spent enough time in the mountains,” he told me, “that I can get from point A to point B safely and efficiently. If shit hits the fan, I could feed my family off the coast. But I'm totally lost in the desert. I don't understand the desert at all.”

In the months leading up to our meeting, Chouinard and Patagonia had seen a few disasters. The Thomas wildfire, the largest in California history, torched the hills around the company's Ventura headquarters. Five employees lost their homes, and then came the mudslides. All of which took place while Patagonia dealt with a crisis back east: a decision by President Trump, the great un-doer, to shrink some of his predecessor's national monuments. The pledge was a first for an American president; limiting the size of monuments like Bears Ears in Utah would mean the largest reduction of protected land in U.S. history. Which is what led Patagonia, in early December, to change its home page to a stark message: “The President Stole Your Land.”

In response, the U.S. House Committee on Natural Resources sent out an e-mail with the subject line “Patagonia: don't buy it.” This wasn't just Trump whining on Twitter that Nordstrom wasn't supporting his daughter's fashion line. The federal government, run by allegedly pro-business Republicans, basically called for the boycott of a privately held company—provoking a former director of the Office of Government Ethics to label the action “a bizarre and dangerous departure from civic norms.”

Chouinard has been known to be a prickly contrarian. He doesn't do e-mail. His cell phone goes largely untouched. But he's adept at delivering powerful sound bites. In December, Chouinard went on CNN—wearing what looked to be the same flannel shirt from the day we met—and said, “I think the only thing this administration understands is lawsuits. We're losing this planet. We have an evil government.… And I'm not going to stand back and just let evil win.”

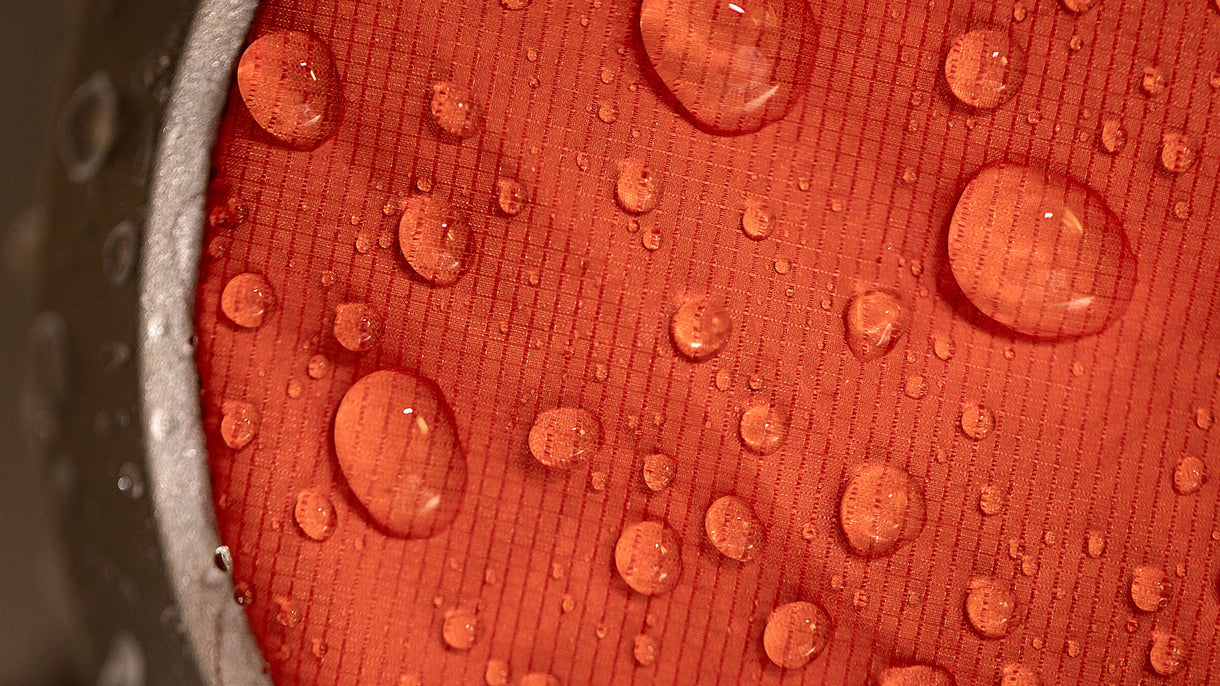

This is not your parents’ fleece-maker. We're past the old jokes about Patagucci or Fratagonia. Sure, you still see a Synchilla vest on every venture capitalist in Palo Alto; not for nothing does the Jared Dunn character on Silicon Valley possess a Patagonia collection supreme. But the vest also crisscrosses popular culture: DeRay Mckesson, one of the faces of Black Lives Matter, wears Patagonia so often his vest has its own Twitter feed. A$AP Rocky shows up in Snap-T sweaters. Louis Vuitton cribbed its Classic Retro-X jacket for a mountaineering look. Universities from Oregon to Ole Miss are Patagonia-saturated, and meanwhile, vintage finds—the rarest featuring the original “big label” logo—fetch a premium on eBay.

The company's HQ looks like a cross between a college campus and a recycling center. Solar panels everywhere. Wet suits drying on the roofs of cars—the five-acre spread is a short walk from the beach. The company has an on-site school where employees can enroll their kids through second grade, one of the reasons that Patagonia has near gender parity among employees. Many of its CEOs have been female, including the current one, Rose Marcario. Chouinard writes in his memoir–cum–business bible, Let My People Go Surfing, “I was brought up surrounded by women. I have ever since preferred that accommodation.”

Building off the momentum around public lands, Patagonia is doubling down on its activist streak. In February, it launched a new online platform to connect customers with environmental groups. This spring it will announce a certification it's spearheading for “regenerative organic agriculture,” Chouinard's latest obsession. That's the practice where farmers, through topsoil management, absorb carbon from the climate. As Chouinard sees it, it's possibly our best shot against climate change—and likely good for Patagonia's bottom line. “In business, this is what we do here—we just break the rules,” he said. “Life is so much easier by breaking the rules than trying to conform to the rules. It's so much easier.”

For a doomsayer on the verge of becoming an octogenarian, Chouinard stays awfully busy: writing op-eds, developing new products, stoking outrage. Assuming he doesn't get cancer from those childhood swims in photo-processing chemicals, I don't just think he'll outlast Trump, who's eight years his junior; he'll probably outlast me, and I'm only staring down 41. The solution, Yvon-style, would appear to be to remain active, to remain engaged. In a 1992 letter to employees titled “The next hundred years,” Chouinard wrote, “I have a little different definition of evil than most people. When you have the opportunity and the ability to do good and you do nothing, that's evil. Evil doesn't always have to be an overt act. It can be merely the absence of good.” The cure is action.

Read the full article here.