On one gloriously wild and environmentally hopeful ski trip in the Arctic fjords of Norway’s Lofoten Islands, the former director of environmental initiatives at Patagonia in Europe, Mihela Hladin Wolfe, finished a presentation on community solar projects, which had been successfully implemented into small Dutch villages. She explained the opportunity and responsibility of community-engaged activism – and then put me on the spot: “Why not Zoe? Why aren’t we doing community solar in Chamonix?”

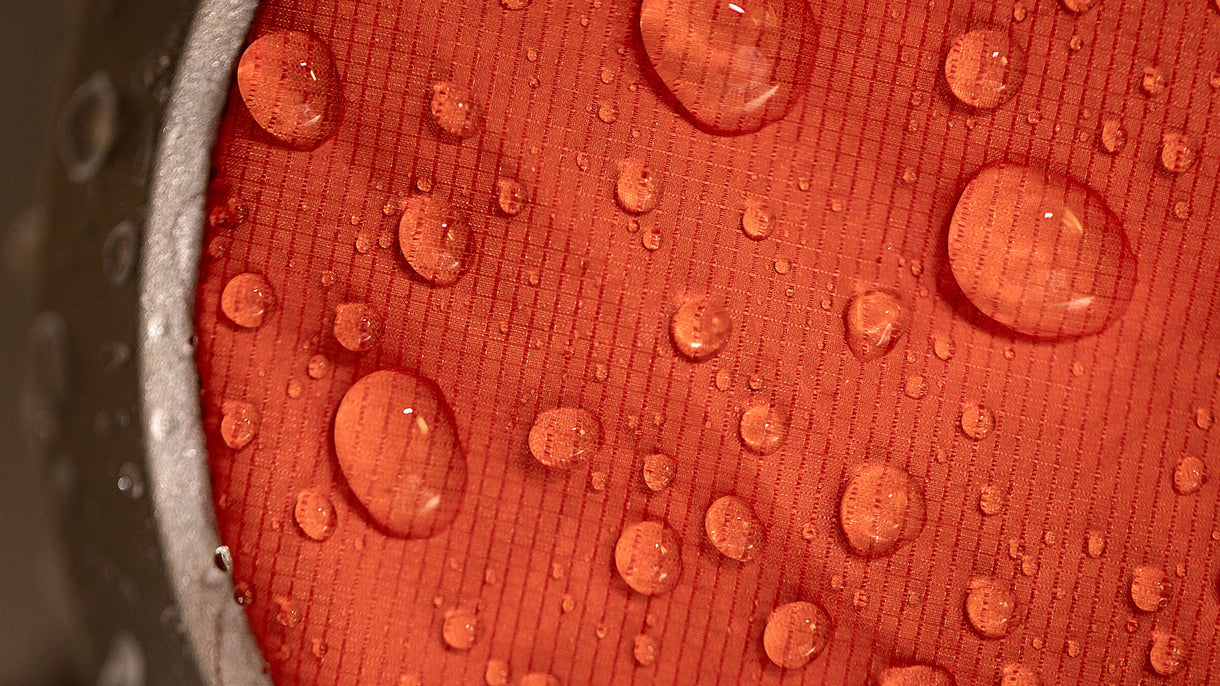

Storm skiing and community-engaged activism. Zoe Hart in Norway’s Lofoten Islands on the trip that hatched Chamonix’s community-energy program. Photo: Jelle Mul

Storm skiing and community-engaged activism. Zoe Hart in Norway’s Lofoten Islands on the trip that hatched Chamonix’s community-energy program. Photo: Jelle Mul

A strong, charismatic Slovenian woman with a list of environmental wins on her resume, Mihela has worked throughout Europe, the US and China on finding solutions to climate change, protecting forests, rivers, critical land and marine habitat, and supporting Regenerative Organic agriculture. She’s a mentor and a friend. And I understand there aren’t any nos in her world of environmental action.

Despite the heaviness of her ask, thinking of my kids and our responsibility to future generations, I had no reason to reject her proposition. If governments are and will be too slow, too burdened by politics and at times corrupt, isn’t saying “yes” the only way we can we take back control of our future?

Mer de Glace, on the northern side of Mont Blanc, is France’s largest glacier and is quickly retreating, like many others in the Alps. Chamonix. Photo: Pierre Cadot

Back in Chamonix, my big mouth and big promises began to sink in. I didn’t understand exactly what community energy meant, how it worked or where to start. My environmental management and sustainable development background was too vast and general. Admittedly, I was not even an engineer or scientifically inclined. So, I started researching and seeking mentors, slowly gathering an understanding of how a renewable-energy community functions and why it is worthwhile.

As it turned out, the concept doesn’t require a fancy background or an education in environmental studies. It’s quite simple: A community of people fund an enterprise or cooperative, donate time, seek rooftops for solar panels, work with towns and the government toward a common goal of renewable energy and, ultimately, find investors. Then the community co-invests in installing solar panels on viable roofs and sells this renewable energy back to the national energy grid. These are not nonprofit endeavors but rather for-profit systems where investors recover a return on their investment. The surplus returns on investments are re-infused into the business, allowing for the project to grow and replace more and more non-renewable energy sources. For people who can’t put panels on their own house and negate their own consumption, it’s like planting a tree somewhere else for one that you cut down. If enough of these projects are founded, demand will significantly decline for non-renewable energy.

I liked the sound of all of this.

Momentum built as I started speaking to friends around me, announcing my intentions. In sharing publicly, I was both committing to myself and beginning to look for partners – people wanting to take responsibility and push change, not just talk about it.

The “anything is possible” American in me is why I landed in Chamonix in the first place. After hearing my peers talk about the mountainous mecca in the French Alps, I spent my first post-university fall back in New Jersey, where I’d grown up, to stockpile money. In January of 2001, I arrived in Chamonix, straight off a plane from Newark. The skies were covered with clouds, the slopes full of snow, and it wasn’t until two weeks later, after stumbling around the ski area solo on a pair of telemark skis, that the most majestic skyline I’d even seen – filled with granite peaks and cascading glaciers – unveiled itself. Chamonix’s peaks and valleys were the catalysts in my path toward mountain guiding and then eventually establishing French residence, growing roots and a family, along with a passion for preserving this beauty for future generations.

Chamonix at its best—with a coat of snow. Snow lines are rising in the mountains surrounding Chamonix, and in the last 50 years, snowfall below 1,000 meters (around 3,281 feet) has dropped by 40 percent. Photo: Thomas Guerrin

Renewable-energy communities (REC) aren’t new in France. There’s Énergie Partagée and Energie Citoyenne, systems that have been established and are already thriving in more than 300 locations across the country. Centrales Villageoises hosts resources and information on all the existing projects, the first of which was up and running in 2014. But renewable-energy communities are a diverse phenomenon, dependent on a range of private and public participants. I was going to need to get socially innovative, and not only mingle with my environmentally involved mountain friends, if I wanted to bring REC to Chamonix.

I figured that raising 500,000 euros (about $600,000), the base required to fund the first project, would be no problem. When I learned that we actually only needed 20 percent of that, and that a bank loan would do the rest, I thought it would be even easier. And luckily, in 2019, while organising Chamonix’s first Running Up for Air trail event, I connected with Chamonix’s mayor, Eric Fournier, who is also the president of the Communauté des Communes de la Vallée de Chamonix-Mont-Blanc*, and was offered an invitation to discuss my intentions as an environmentalist in the valley. Now I knew what I’d do with that opportunity.

Weather systems move quickly in the mountains; can the community of Chamonix move quick enough to do their part against climate change? Solar energy is one viable piece of the solution in the valley. Photo: Pierre Cadot

Upon meeting Fournier, I realised I’d entered into politics and policy and system change in a country of which I am not a citizen and in a language that I will always be learning. Nuances of polite politics in French are beyond me. I often address issues which are off limits or ask questions which want to be left unsaid. When Fournier asked what my intention in the valley was, I said, “To change things and to impact the environment in a positive way for the future of my children and the next generation.” But the question remained: Was my need for changing his town an insult or an inspiration?

Whispers that others in the Chamonix Valley were equally interested in REC started to come my way, and so I managed to invite myself to a town meeting that included government officials, nonprofits, energy providers and community-energy experts—all the main players involved in the town’s second attempt at launching a citizen-energy project. (I learned there was an attempt to launch a project a year earlier, but it never came to fruition.) I was the last one to arrive, just a few minutes late. All eyes were on me as I took my chair. This was not the first, or last, time that I would be the only foreigner in the room. It was uncomfortable, but I am getting more comfortable in uncomfortable spaces.

Chamonix was willing to support but not carry the project. Experts conversed around me, and for the first time since I had started learning about community energy, I was able to understand the facets of the discussion and even offer clarification or information to some of the less knowledgeable folks. I left the meeting feeling more hopeful than ever.

Until it all came to a screeching halt.

Bureaucracy, money, time, interest and conflict of vision completely stalled the project in a few months. Volunteers wanted to be paid before the project was even in place, yet there was no money to pay them with. And as of that moment, there was no real project to be paid for. The town wanted to see it unfold before committing. And then, elections happened. Municipal elections crept upon us, and I learned that in France the current government cannot engage, or even exchange, in any new projects for six months before an election. After almost a year, nothing was done. My team dissipated. Anyone connected to the town was either unable to work with me or unwilling.

The longest, most committing climb I have ever done is Deprivation, on the north face of Mount Hunter in Alaska, in 2008. After one failed attempt with my best friend and climbing partner, Sue Nott, I went back with Max, my now husband. We packed light and went fast. At some point in the climb, I realised going down would be harder than going up. We went for 43 hours straight, with a small break to melt water, high up on the face in a wave-like cornice.

Much like the solar project, my first attempt was cumbersome and slow, too heavy with too little experience, and I was destined to fail. After gaining knowledge and experience, a year later, Max and I stood on top of the summit, having climbed faster than any previous party. When we made it back to the bottom of the face, hallucinating with exhaustion, I looked at Max and said, “What is the name of that climb again?” He laughed and said, “Now I know why Mark Francis Twight named it Deprivation.” We laughed together, soon melting into our sleeping bags back at the Kahiltna Glacier Base Camp. The real success of the climb was showing how much is possible.

Deprivation—where grit and perseverance are learned. The author amidst the lessons. Photo: Maxime Turgeon

I had said aloud and promised Mihela, and also silently in my heart to my kids, to see the community-energy project through. I wanted to give my children the gift of sharing with their own kids what I’d grown up with – a tainted, but not yet destroyed, planet.

Chamonix couldn’t continue with the project, but I could. This is the most phenomenal facet of community energy – it is something that we have the right to do on our own, or with the support of the individuals around us. It is something that we can do above and beyond government. When I say this, I don’t mean in the face of the government, but really that it’s our duty, and right, to do more to speed up this whole process of protecting the planet we live on. We can’t sit back. In many ways, it’s already too late.

“This is the most phenomenal facet of community energy—it is something that we have the right to do on our own, or with the support of the individuals around us.”

In the spring of 2019, my REC partners and I received our first feasibility study donated by Haag&Baquet, a local progressive architecture firm partnering with our project. We signed the papers to establish a nonprofit called Mont Blanc 2.0, the version of the Mont-Blanc region we hope to see in the future – which of course includes the revolution of a people-powered energy system. With two grants awarded from 1% for the Planet, we’ve launched into a valley-wide study.

In September 2020, we publicly announced Mont Blanc 2.0 at a three-week-long community event, Le Temps des Possibles. And within days, the Communauté des Communes de la Vallée de Chamonix-Mont-Blanc declared their intentions to help facilitate development for a citizen-led renewable-energy project in the Chamonix Valley. Public appetite was and is still rising.

The Mont Blanc 2.0 nonprofit will live alongside the eventual creation of a for-profit enterprise that we will set up for the Chamonix Valley’s community-energy program. Money that we create will decide what our future valley looks like. It will allow people to engage in action-based solutions easily. And it will give power, and take responsibility, for all that the government can’t or won’t do. It will allow us to acknowledge that it’s not enough to wait for the powers that could be, but it’s our responsibility to facilitate change.

*The Chamonix Valley is a small valley at the base of sharp granite needles and hanging glaciers in the French Alps. Spanning approximately 30 kilometers (around 18 miles), it is comprised of four main villages: Servoz, Les Houches, Chamonix-Mont-Blanc and Vallorcine. The governing body of the valley, comprised of elected officials in each town, is called the Communauté des Communes de la Vallée de Chamonix-Mont-Blanc. To most international travelers, the greater valley is most commonly referred to as “Chamonix.

Image Banner: The sun shines over the Chamonix Valley, powering homes, schools and businesses through 10 rooftop sites harnessing solar energy. Communauté des Communes de la Vallée de Chamonix-Mont-Blanc owns and runs the energy here in this part of the French Alps, providing a positive solution for the people that are witnessing climate breakdown firsthand in the snowpack and glaciers above their homes Photo: Pierre Cadot

____________________________________________________________________

Author Profile

the fourth American woman to earn her International

Federation of Mountain Guides Associations

status. When she’s not guiding or climbing in her

backyard, Chamonix, France, Zoe’s on

international expeditions or climbing trips

throughout North America.