Out of necessity, Jacqueline Sangueza loved fishing nets before she loved the ocean.

Words by Jacqueline Sangueza as told to Andrew O’Reilly

All photos by Jürgen Westermeyer

Many of the people I have worked with over the years tell me about their lifelong love for the ocean, or of the peace they find when out on a boat, or the spiritual connection they have had their entire lives with the sea. But for me, that is not the case. My reasons for getting involved in the fishing-net industry are much more mundane and much more out of necessity.

To start, I wasn’t born anywhere near the ocean. I’m from a small country town in Chile called Monte Águila, which is around 100 kilometers (62 miles) from the Pacific Ocean, and the closest body of water is a tiny stream north of town. There wasn’t much work there, so when I was young, my family moved to Concepción in the hopes of more opportunities. But bad luck struck almost from the moment we arrived. First, my father disappeared, and soon after my only brother was killed in a motorcycle accident. From then on it was my mother, my three sisters and myself all struggling to make ends meet.

This is what I mean when I say I started working in the fishing-net industry out of necessity. The nets and the sea were what gave us our daily money and kept food in our bellies, so I did anything I could to help my family: I washed ships, unloaded cargo, cleaned nets, loaded gear. It was a tough life, but it kept my family fed so I continued doing it. Now, I’ve been working in one part of the industry or another for around 30 years.

Jacqueline and her team cut the nets for further cleaning at Bureo’s warehouse in Talcahuano, Chile.

Jacqueline and her team cut the nets for further cleaning at Bureo’s warehouse in Talcahuano, Chile.

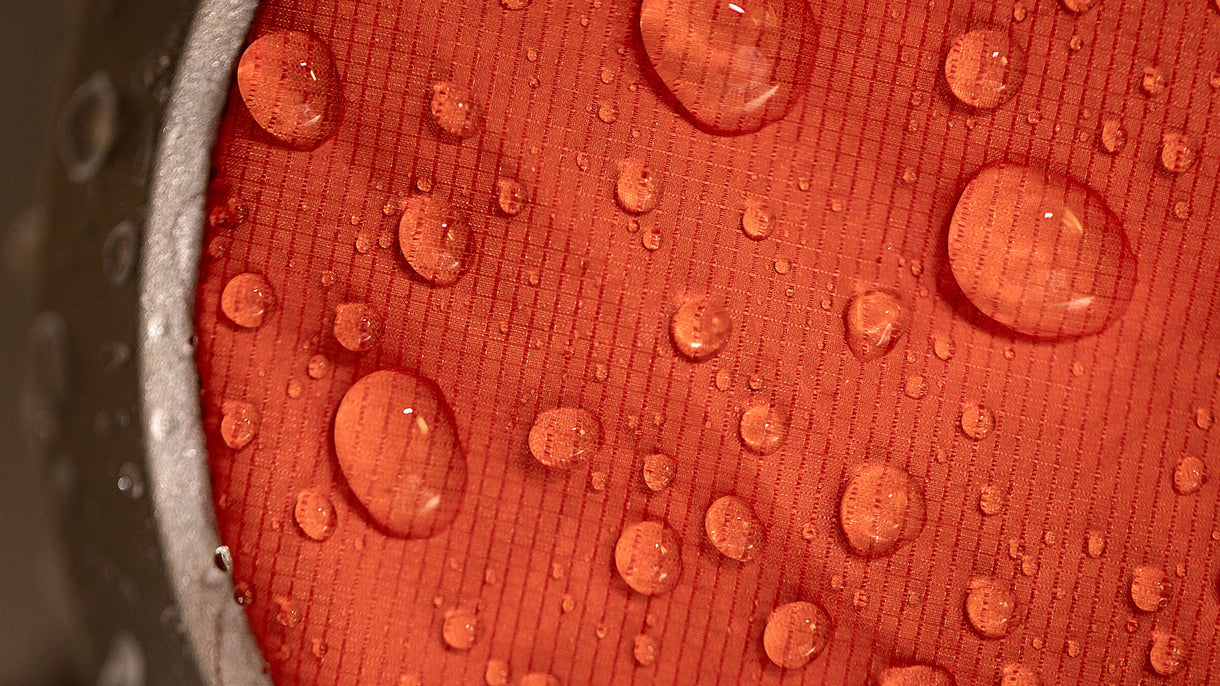

Jacqueline partners with Bureo to put used nylon nets that might otherwise pile up on fishing boats to use.

Jacqueline partners with Bureo to put used nylon nets that might otherwise pile up on fishing boats to use.

There have been many times when I wanted to quit, when I wanted to give it all up. But over time, I have developed a real love for what I do—for the craftsmanship that goes into making nets, to repairing them, to ensuring that they can hold the tonnage of fish. It may seem silly to fall in love with fishing nets of all things, but I have.

During the time I’ve worked with fishermen in Chile, I have also seen a huge number of changes in the industry—some good, some bad. The industry has become much more commercialized and much bigger. This has brought a good deal of money into the country, but it has also caused major environmental impacts. The trash and chemicals that are tossed overboard have only increased with the growth of the fishing industry. It’s a major blow to the marine environment, and the industry itself does not even realize the impact it has because their focus is purely material: more nets, more fish, more money.

Seeing the materialistic drive of the industry and its wastefulness is a big reason why I am working with Bureo to prepare “end of life” nets for the next stage in the recycling process. At first, I was just giving Bureo the nets that we could not repair—the ones that were too old or ruined—because I had no use for them, but then as I began to learn about Bureo’s work, and how they turn what is basically trash into beautiful clothing or a skateboard, I wanted to help them even more.

Used nylon nets hang to dry at Bureo’s warehouse.

Used nylon nets hang to dry at Bureo’s warehouse.

Nylon nets await the shredding process.

Nylon nets await the shredding process.

Luckily for me, I’ve been blessed to be able to continue my net-repair business alongside my work running a team to sort, cut and clean the discarded nets. For me, it’s a win-win situation—I can continue the business that has become a true passion of mine and I can help save Chile’s marine life by both fixing nets and making sure the discarded ones go to Bureo.

When I look back at the person I was three decades ago, I have to laugh. I was a girl who didn’t care about the ocean, had no connection to it and just wanted to earn a living and help my family. But ask me now my thoughts on the sea and I’ll tell you that of all the incredible places we have in Chile, the ocean is the most special to me. It is an ecosystem that is so vital to all our lives and one that I have developed a very close relationship with. But it is also the one place that needs the most help and protection from us.

Jacqueline Sangueza inspects nylon nets during the drying process at Bureo’s warehouse in Talcahuano, Chile.

Jacqueline Sangueza inspects nylon nets during the drying process at Bureo’s warehouse in Talcahuano, Chile.

Curious how recycled fishing nets are being used in consumer goods? Bureo’s NetPlus® material is featured in a range of products, like Patagonia clothing and hat brims, Costa sunglasses, Carver skateboards, Trek bike parts and Futures surf fins—even Jenga games.

Andrew O’Reilly is a Los Angeles-based journalist and writer whose work has appeared in The New York Times, Outside, ESPN The Magazine, Rock and Ice and other publications. When he’s not busy pounding away on a keyboard, he’s skiing or mountain biking in California’s Eastern Sierra.